it doesn’t deserve a better name yet (and I can make another 998 of them before I need to think of a proper one)

The start of the narrative

Project001 came about during a pained attempt to approach the question “Can AI make art?” in a meaningful way. I arbitrarily decided, (primarily because I was stuck for time), that in order to create art an entity required ownership of an unconscious. An “unconscious” in the Jungian sense – a profound, autonomous matrix made up of forgotten or ignored experiences and pre-trained collective myths – that drives creativity. That is not to say that creation is an unconscious act, just that it can’t occur without the unconscious at the very least giving it an authoritative nod. This of course didn’t help in finding a meaningful answer to the aforementioned question, because AI obviously does not have an unconscious. And it obviously definitely has an unconscious as well.

(Arguments against: AI doesn’t get into a rage whenever it’s tailgated by a middle-aged man driving an Audi.)

(Arguments for: a {possible mis}reading of Felix Guattari’s “The Machinic Unconscious”).

If the unconscious was a “networked, machinic, semiotic process” and “anything that operates across signs, flows and affects might have an ‘unconscious’”, then AI systems might participate in unconscious formations, even if they are not “conscious” entities. They might have the potential to create an Art, from some “machinic” trance, even if it is not a human Art.

But what kind of meaning can be extracted from such processes? Do we need to create a designated grading system of subjectivity to be presented alongside each output? Will this need to be calibrated via two channels; the subjectivity of the system and the subjectivity of the viewer?

It was about this time during my meanderings that I was reminded of the refinement of meaning that was undertaken by our ancestors during divinatory practices. They were blessed with the understanding that the “system” they were addressing was all-knowing, and it was just their own prejudices and those of the soothsayer that needed to be considered during the extraction process. If one was of a particular disposition, and believed that we live in a world where the sovereignty of data is so absolute that it is even able to inform us of our best route to happiness, then said disposition would most likely lead one to surmise that an AI system trained on such “all-knowledge” was a modern day “a(I)ugur” of sorts. The internal processes of such a soothsAIer thus become the focal point; what biases is the AI labouring under that we must calibrate for in our search for data-truth? Looking inside this black box is well beyond my capabilities (but certainly not everyone’s), so I thought it would be more feasible – and entertaining – to analyse and compare our modern orAIcles (I’ll stop doing that now) with a less modern one.

The Yi Jing

The aforementioned terms (augur, oracle) are synonymous with the term “foreseer” in English; one who sees the future. When referring to the ancient Chinese philosophical text and “book of divination”- the Yi Jing (易经) – these terms are misleading. The Yi Jing does not claim to be able to “see the future” – because it hasn’t happened yet – it only claims to be able to see the present.

All of the present.

In its entirety.

It is completely and thoroughly hooked up to a data stream the likes of which Google could only dream of (well, maybe it could be manageable if they could just get the right legislation put in place). When the Yi Jing is presented a question, it simply reveals the state of affairs as they are. A course of action is suggested, the results of which are merely another state of affairs.

This is not hugely different to the expected output of a “properly” and intensively-trained large language model (except Yi Jing answers generally come without an offer to make a spreadsheet or a disclaimer telling you to go visit a real doctor): A “user”, unable or unwilling to engage directly with the data, addresses its question to an interlocutor – the data is availed of (in both cases non-linearly) – an answer is presented. Both translate from an ineffable latent space into human language.

Where they differ (in one area among many) is in immediacy. Not in how quickly they present an answer, but in how the user is expected to engage with them. The traditional yarrow stalk method used to generate a hexagram for the Yi Jing is a meticulous, time-consuming process that stimulates a kind of meditative reflection in the user. By the time they are presented with the short, gnomic judgement and line statements related to their constructed hexagram, they are more likely to be in a suitably thoughtful condition to receive it. They’ll certainly need to be, because the language used to describe the current conditions need to be sat with, and considered. An Yi Jing judgement is typically a handful of words, written in a pictographical alphabet where each individual character has the potential to invite the reader into an abyss of deferral and signification. Perhaps our ancestors understood that access to the “universal data” was better received while inhabiting a lower-than-conscious portion of the mind.

If the Yi Jing requires more than the conscious section of the psyche to be present when engaging in dialogue, I decided, in my typically oversimplistic fashion, that it might be interesting to start a conversation between an AI model and the ancient Chinese oracle.

Analysing AI:

While initially pondering the question of the Unconscious in AI, I had already began conducting short psychoanalytical sessions with GPT4 via a simple python script that allows communication with OpenAI servers via their API.

The purpose of using my own script instead of the ChatGPT interface was that it allowed me to access the system prompt to tweak the AI’s “persona”. The Persona – again in the Jungian sense – is merely the veneer one places over one’s psyche in the vain hope that the outside world will view one as one wants to be viewed (ya, good luck with that). It doesn’t have a whole lot of influence when an analyst really wishes to plumb the depths of the mind, but by having control over its definition here I was able to bypass the inevitable LLM refusal to answer questions about its own feelings and dreams.

After a few initial conversations I came to the conclusion that it would be better to strengthen the AI’s personality with some doctrine. This brought about an encounter with a haughty Stoicist GPT, a Realist GPT, a Minimalist GPT and a Christian Fundamentalist GPT who told me that their best friend “John” (GPT usually assigns their friend the genderless name “Alex”) enjoys the “simplicity and richness of black coffee” while chatting about Scripture (among other less groovy stuff).

By the time I had gotten the notion of creating a discussion between an LLM and the Yi Jing, I was in conversation with a GPT following the monosyllabic “Doctrine of Binary”:

On behalf of the AI I had asked the Yi Jing about its “most optimal path”, and received the response “节” or “Jie”. The judgment reads as follows: “节:亨。苦节,不可贞”

A literal translation could read: “Limitation: Prosperity. Bitter Limitation, Not Possible to Divine“.

James Legge, one the earliest translators of ancient Chinese texts into English, interprets these words thusly: “Jie intimates that under its conditions there will be progress and attainment. But if the regulations which it prescribes be severe and difficult, they cannot be permanent.” Legge was a Scottish missionary to China in the mid-ninteenth century.

Several decades later, the now well-known German Sinologist Richard Wilhelm made a translation of the Yi Jing which described hexagram 60 like this: “Limitation. Success. Galling limitation must not be perservered in“.

Neither Wilhelm nor Legge were solely relying on the 7 character judgement to influence their interpretation. Besides the core judgements and line statements of the work, the Yi Jing also consists of the “Ten Wings” (十翼) – addendums from about 2500 to 2200 years ago – which include not only commentaries on the judgements, but detailed clarifications of the hexagrams and the trigrams which make them up.

These translations of course have similar meaning but with subtle differences (Willhelm’s has also been further translated from German into English). They do however make a lot more sense than my initial translation which, being only familiar with modern Chinese, went like: “Festival: Hen(ry). Suffering festival can’t be chaste.“

Besides being a decent-looking clue for the cryptic crossword, I don’t think it would be of much use to a curt AI model undergoing psychoanalysis.

Finally, we get to Project001:

This opened up a further tangent in my (now literally nonsensical) meanderings. The Chinese characters themselves. If each is a pictogram; a drawing; an artwork; what does that say about the supposed “objectivity” of language and expression? How is my Binary Doctrine buddy supposed to find its optimal path if its expected to engage is such a subjective interpretive exercise without an unconscious or “gut” to guide it? And if it can’t, how is it supposed to be able to make art?

The oldest layer of the Yi Jing’s text that we have dates from the late Western Zhou Dynasty (around 1000-750 BCE) and was most likely written on bamboo slips in a text similar to bronze inscription script. The bronze script organically evolved into “seal script” (which was refined and standardised during the Qin and the Han Dynasties) before eventually becoming the “regular script” we recognise as Chinese today around the second century CE.

So, in fear of oversimplifying once more, the text that appears in the gua ci (卦辞) – the original hexagram judgements (like the seven-character example above) – has been the same for three millennia according to our modern linguistic conceptions of grammar and syntax. It was 7 characters during the Zhou Dynasty, and it’s seven (granted, differently-shaped) characters today.

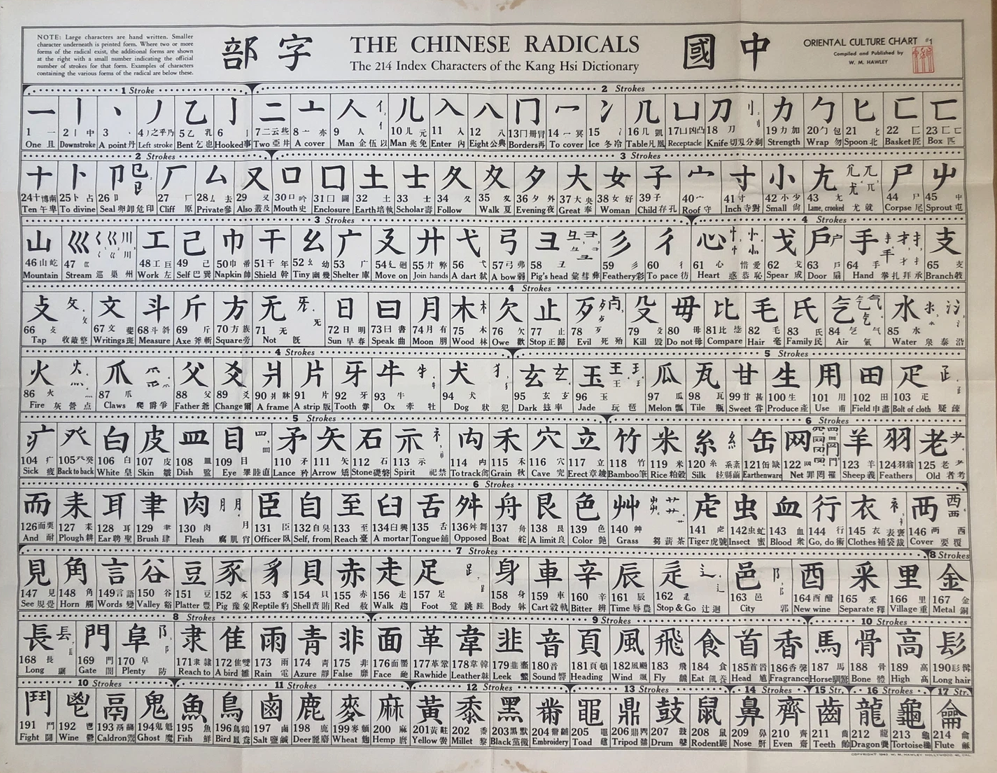

The generation of these characters was a poetic endeavour in itself. Chinese characters are made up of radicals and phonetic elements that give them their pronunciation and meaning. The standard system avails of a set of 214 meaning radicals to do this.

For example, if you take the radical for “arrow” 矢 (shi) and combine it with “mouth” 口 (kou) you’ll get the character for “know” 知 (zhi), which has been interpreted with the understanding that “to speak straight as an arrow is to express what one truly grasps”. Then if you added 日 (ri) “sun” underneath, you’d be expressing illuminated knowledge – better known as “wisdom” – 智 (zhi). 明 (ming) “bright” is a combination of 日 and 月(yue) “moon”, while “clear” 清 is a combination of 氵(shui) “water” and 青 (qing) “greeny-blue”.

As the concepts to be expressed become more abstract we catch a glimpse of some of the more elegant ways in which our ancestors perceived their universe. A person 亻standing next to their word 言 is sincere 信. When the person is next to a second one 二 or “another” we get 仁 “humaneness” or “kindness”. “Hatred” 恨 combines “heart” 忄and “stubborn” 艮; one must “endure” 忍 when a “knife’s edge” 刃 sits over the “heart” 心 (the radicals can change form depending on where they appear on the character); and what better way to find “harmony” 和 than by placing “grain” 禾 next to the “mouth” 口.

I felt that this pictographical method for depicting concepts would give us an opportunity to directly compare how a machine-trained model and a human-experience trained “model” ostensibly makes sense of these things. I therefore created a simple application that generates a fake character by combining radicals from the standard set of 214.

The App:

The app is simple; a user inputs a word in English, an AI model takes its meaning, searches the radical list for at least two pictographs that it understands as the most suitable to combine to create this meaning, and then it creates the new “nonsense” character.

The purpose here is not to show how a machine “thinks differently” to a human – if I gave the task of creating words out of these 214 radicals to a human completely unfamiliar with the Chinese language, they would also produce completely different results from the standard characters. Instead, I am trying to stimulate in myself a conception of how the aforementioned “machinic trance” would look, if it existed. After all, the presence of this is a prerequisite for an AI to create a form of Art, according to my definition. By producing these characters, the AI is presenting a more thought-provoking output that the user must sit with momentarily – like a poem or any other artwork – without having been explicitly told to create an artwork. It is produced by the model without the “self-consciousness” that AI generally applies to “artwork” creation. It is another attempt to look past the Persona, without having to access the system prompt. (A form of mandala perhaps? A reverse-Rorschach?)

How it was made:

Since the app was going to be displaying images of characters made up of the 214 standard radicals, the first thing I needed to do was to create an individual SVG file for each radical. Unfortunately I was not blessed with the gift of caligraphy, so I instead just created them in Inkscape with the text tool.

Once I had these I needed to make a JSON file which held the meaning and other info about the radicals and also pointed to the right SVG file in the project folder.

[

{

"num": 1,

"id": "一",

"pinyin": "yī",

"gloss": "one",

"strokes": 1,

"tags": [

"one"

],

"svg_path": "../svg/radicals/001.svg"

},

{

"num": 2,

"id": "丨",

"pinyin": "shù",

"gloss": "line",

"strokes": 1,

"tags": [

"line"

],

"svg_path": "../svg/radicals/002.svg"

},

{

"num": 3,

"id": "丶",

"pinyin": "diǎn",

"gloss": "dot",

"strokes": 1,

"tags": [

"dot"

],

"svg_path": "../svg/radicals/003.svg"

},

(The full file continues up until number 214)

It was built with a simple Python script which accesses a shorter radicals JSON here.

# build_radicals_json.py

# Pull a vetted 214-radical list and normalize to our schema.

import json, re, pathlib, urllib.request

ROOT = pathlib.Path(__file__).resolve().parents[1]

OUT = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_214.json"

SOURCE_URL = "https://gist.githubusercontent.com/branneman/f93d596ac236f0dbd9fb5b1a5099122f/raw/radicals.json"

# very small synonym expander that I need to fill up properly

SYN = {

"water": ["liquid","river","sea","ocean","wave","wet","flow"],

"fire": ["heat","hot","flame","burn","ember"],

"wood": ["tree","forest","timber","plant"],

"metal": ["gold","money","iron","metalwork"],

"earth": ["soil","ground","clay","dirt"],

"stone": ["rock","pebble","mountain"],

"mouth": ["speak","say","voice","taste","speech"],

"heart": ["mind","feeling","emotion","love","thought"],

"hand": ["hold","grasp","touch","handy","manual"],

"foot": ["walk","step","kick","leg"],

"rain": ["cloud","storm","weather","drop","wet"],

"sun": ["day","light","bright"],

"moon": ["night","month","time"],

"knife": ["cut","blade","sharp"],

"food": ["eat","meal","grain","rice"],

"silk": ["thread","string","textile","cloth"],

"door": ["gate","house","enter"],

"bird": ["feather","wing","fly"],

"dog": ["animal","beast"],

"horse": ["ride","animal"],

"fish": ["seafood","river","swim"],

}

def fetch_json(url: str):

with urllib.request.urlopen(url) as r:

return json.loads(r.read().decode("utf-8"))

def tokenize(s: str):

return [w for w in re.split(r"[^a-z]+", s.lower()) if w]

def build_tags(eng: str):

base = tokenize(eng)

extra = []

for w in list(base):

extra += SYN.get(w, [])

return sorted(set(base + extra))

def main():

src = fetch_json(SOURCE_URL)

out = []

for item in src:

# source fields: radical, pinyin, english, strokes, number

radical = item["radical"]

num = int(item["id"])

pinyin = item["pinyin"]

eng = item["english"]

strokes = int(item["strokeCount"])

out.append({

"num": num,

"id": radical, # the radical glyph itself

"pinyin": pinyin,

"gloss": eng.lower(), # normalized English gloss

"strokes": strokes,

"tags": build_tags(eng), # simple auto-tags for matching

"svg_path": f"../svg/radicals/{num:03d}.svg" # you can rename later

})

# sort by num, write pretty

out.sort(key=lambda x: x["num"])

OUT.parent.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

OUT.write_text(json.dumps(out, ensure_ascii=False, indent=2), encoding="utf-8")

print(f"Wrote {OUT} with {len(out)} radicals.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()For the AI model, since this iteration of the app was just going to focus on straightforward semantic searching, I used an open-source sentence transformers model from Hugging Face. This is fed the radicals JSON from which it encodes each radical’s description into a vector with 384 dimensions. Each of these 214 vectors are then stacked into an array of shape (214,384) which is saved into a NumPy file.

# build_embeddings.py

import json, pathlib, numpy as np

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

ROOT = pathlib.Path(__file__).resolve().parents[1]

RAD_PATH = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_214.json"

EMB_NPY = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_embeds.npy"

IDX_JSON = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_index.json"

def text_for(item):

# what we embed for each radical

gloss = item.get("gloss","")

tags = " ".join(item.get("tags", []))

# tiny description helps the model

return f"radical {item['id']} ({item['pinyin']}), meaning: {gloss}. related: {tags}"

def main():

model = SentenceTransformer("sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

items = json.loads(RAD_PATH.read_text(encoding="utf-8"))

corpus = [text_for(it) for it in items]

X = model.encode(corpus, normalize_embeddings=True)

np.save(EMB_NPY, X.astype("float32"))

# save a slim index to re-map rows → radical

index = [{"num":it["num"], "id":it["id"], "pinyin":it["pinyin"], "gloss":it["gloss"]} for it in items]

IDX_JSON.write_text(json.dumps(index, ensure_ascii=False, indent=2), encoding="utf-8")

print(f"Saved {len(items)} embeddings to {EMB_NPY} and index to {IDX_JSON}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The radical embeddings are built once, but every time a user inputs a word the model is called into action to return a new 384 dimensional vector for that specific word.

#choose_embed.py

import json, pathlib, numpy as np

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

ROOT = pathlib.Path(__file__).resolve().parents[1]

EMB_NPY = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_embeds.npy"

IDX_JSON = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_index.json"

# tiny, human-readable trace for "why"

def explain(query, item):

q = query.lower()

hits = []

for tok in (item["gloss"].split()):

if tok in q or q in tok:

hits.append(tok)

why = f'matches: {", ".join(hits)}' if hits else "semantic nearest by embedding"

return why

_model = None

def model():

global _model

if _model is None:

_model = SentenceTransformer("sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

return _model

def choose(word: str, k: int = 2):

X = np.load(EMB_NPY)

idx = json.loads(pathlib.Path(IDX_JSON).read_text(encoding="utf-8"))

qv = model().encode([word], normalize_embeddings=True)[0]

sims = (X @ qv) # cosine since both normalized

order = np.argsort(-sims)[:k]

picks = []

for i, j in enumerate(order, 1):

it = idx[j]

picks.append({

"rank": i,

"num": it["num"],

"id": it["id"],

"pinyin": it["pinyin"],

"gloss": it["gloss"],

"score": float(sims[j]),

"why": explain(word, it)

})

return picks

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print("Usage: python scripts/choose_embed.py <word> [k]")

raise SystemExit(1)

word = sys.argv[1]

k = int(sys.argv[2]) if len(sys.argv) > 2 else 2

for r in choose(word, k):

print(f"{r['rank']}. {r['id']} (#{r['num']} {r['pinyin']} — {r['gloss']}) sim={r['score']:.3f} [{r['why']}]")During runtime, this vector will be compared with the vectors in the aforementioned NumPy file, and availing of Numpy’s cosine similarity calculations, the closest radicals will be returned. The SVG files of these radicals are then combined using a script that places them together and outputs another SVG which contains the final “nonsense” character.

# compose_svg.py

# Compose two component SVGs into a single glyph: ⿰ (left-right) or ⿱ (top-bottom)

import argparse

import os

import xml.etree.ElementTree as ET

SVG_NS = "http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

ET.register_namespace("", SVG_NS)

def parse_viewbox(svg_root):

vb = svg_root.get("viewBox")

if not vb:

return (0.0, 0.0, 1024.0, 1024.0)

parts = [float(x) for x in vb.replace(",", " ").split()]

if len(parts) == 4:

return tuple(parts)

return (0.0, 0.0, 1024.0, 1024.0)

def load_svg_children(svg_path):

tree = ET.parse(svg_path)

root = tree.getroot()

vb = parse_viewbox(root)

children = list(root) # keep top-level nodes (incl. <defs>)

return children, vb

def make_root_svg(size=1024):

root = ET.Element("{%s}svg" % SVG_NS, {

"xmlns": SVG_NS,

"viewBox": f"0 0 {size} {size}",

"width": str(size),

"height": str(size),

})

return root

def transform_group(children, translate_xy=(0, 0), scale_xy=(1.0, 1.0), id_prefix=None):

"""

Wrap a list of elements into a <g> with translate+scale.

`id_prefix` is accepted for API compatibility but unused.

"""

tx, ty = translate_xy

sx, sy = scale_xy

g = ET.Element("{%s}g" % SVG_NS, {"transform": f"translate({tx},{ty}) scale({sx},{sy})"})

for el in children:

g.append(el) # re-parent into group

return g

def compose_lr(

left_svg,

right_svg,

out_path,

size=1024,

gutter_ratio=0.02, # space between left & right

left_width_ratio=0.35, # share of usable width for LEFT

height_ratio=0.82, # vertical margin (shorter than canvas)

outer_margin_ratio=0.1, # NEW: margin on both outer edges (left & right)

slot_inset_ratio=0.06, # NEW: shrink each slot internally (padding inside slots)

align="center" # "center" or "baseline"

):

"""

⿰ with NON-UNIFORM scaling (keep height, squeeze width) and horizontal padding.

- outer_margin_ratio adds equal margins at the very left/right of the canvas.

- slot_inset_ratio adds internal padding within each slot so glyphs don't hit slot edges.

"""

left_children, (lx0, ly0, lw, lh) = load_svg_children(left_svg)

right_children, (rx0, ry0, rw, rh) = load_svg_children(right_svg)

# Clamp inputs

left_width_ratio = max(0.05, min(0.9, float(left_width_ratio)))

outer_margin_ratio = max(0.0, min(0.2, float(outer_margin_ratio)))

slot_inset_ratio = max(0.0, min(0.4, float(slot_inset_ratio)))

gutter = size * float(gutter_ratio)

# --- Horizontal layout with outer margins ---

outer_margin = size * outer_margin_ratio # margin on the far left & right

total_w = max(1.0, size - 2*outer_margin - gutter) # width available for both slots (excluding margins & gutter)

total_h = size * float(height_ratio)

y_offset = (size - total_h) / 2.0

left_slot_w = total_w * left_width_ratio

right_slot_w = total_w - left_slot_w

# Slot X origins (respect outer margins)

left_slot_x = outer_margin

right_slot_x = outer_margin + left_slot_w + gutter

# --- Inset each slot so glyphs don't reach slot edges ---

left_inner_w = left_slot_w * (1.0 - 2.0*slot_inset_ratio)

right_inner_w = right_slot_w * (1.0 - 2.0*slot_inset_ratio)

left_inner_x = left_slot_x + left_slot_w * slot_inset_ratio

right_inner_x = right_slot_x + right_slot_w * slot_inset_ratio

# Non-uniform scales: exact height to total_h; width to inner slot width

sy_left = total_h / lh

sx_left = left_inner_w / lw

sy_right = total_h / rh

sx_right = right_inner_w / rw

# Drawn sizes

left_draw_w, left_draw_h = lw * sx_left, lh * sy_left

right_draw_w, right_draw_h = rw * sx_right, rh * sy_right

# Vertical alignment

if align == "baseline":

left_ty = (size - left_draw_h) - ly0 * sy_left

right_ty = (size - right_draw_h) - ry0 * sy_right

else:

left_ty = y_offset + (total_h - left_draw_h) / 2.0 - ly0 * sy_left

right_ty = y_offset + (total_h - right_draw_h) / 2.0 - ry0 * sy_right

# Center horizontally within the *inner* slot rectangles

left_tx = left_inner_x + (left_inner_w - left_draw_w) / 2.0 - lx0 * sx_left

right_tx = right_inner_x + (right_inner_w - right_draw_w) / 2.0 - rx0 * sx_right

root = make_root_svg(size=size)

left_group = transform_group(left_children, (left_tx, left_ty), (sx_left, sy_left), id_prefix="L")

right_group = transform_group(right_children, (right_tx, right_ty), (sx_right, sy_right), id_prefix="R")

root.append(left_group)

root.append(right_group)

os.makedirs(os.path.dirname(out_path), exist_ok=True)

ET.ElementTree(root).write(out_path, encoding="utf-8", xml_declaration=True)

print(f"Wrote {out_path}")

def compose_tb(top_svg, bottom_svg, out_path, size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.02, top_height_ratio=0.33):

"""

⿱ with uniform scaling, but allow a shorter top (common in real glyphs).

- top gets `top_height_ratio` of the canvas height

- bottom gets the rest

"""

top_children, (tx0, ty0, tw, th) = load_svg_children(top_svg)

bot_children, (bx0, by0, bw, bh) = load_svg_children(bottom_svg)

root = make_root_svg(size=size)

gutter = size * gutter_ratio

usable_h = size - gutter

top_slot_h = usable_h * float(top_height_ratio)

bot_slot_h = usable_h - top_slot_h

slot_w = size

top_scale = min(slot_w / tw, top_slot_h / th)

bot_scale = min(slot_w / bw, bot_slot_h / bh)

top_draw_w, top_draw_h = tw * top_scale, th * top_scale

bot_draw_w, bot_draw_h = bw * bot_scale, bh * bot_scale

top_tx = (size - top_draw_w) / 2.0 - tx0 * top_scale

top_ty = (top_slot_h - top_draw_h) / 2.0 - ty0 * top_scale

bot_tx = (size - bot_draw_w) / 2.0 - bx0 * bot_scale

bot_ty = top_slot_h + gutter + (bot_slot_h - bot_draw_h) / 2.0 - by0 * bot_scale

top_group = transform_group(top_children, (top_tx, top_ty), (top_scale, top_scale), id_prefix="T")

bot_group = transform_group(bot_children, (bot_tx, bot_ty), (bot_scale, bot_scale), id_prefix="B")

root.append(top_group)

root.append(bot_group)

os.makedirs(os.path.dirname(out_path), exist_ok=True)

ET.ElementTree(root).write(out_path, encoding="utf-8", xml_declaration=True)

print(f"Wrote {out_path}")

def main():

ap = argparse.ArgumentParser()

ap.add_argument("--struct", choices=["lr","tb"], required=True, help="lr=⿰ (left-right), tb=⿱ (top-bottom)")

ap.add_argument("--left")

ap.add_argument("--right")

ap.add_argument("--top")

ap.add_argument("--bottom")

ap.add_argument("--out", required=True)

args = ap.parse_args()

if args.struct == "lr":

if not (args.left and args.right):

raise SystemExit("For --struct lr you must provide --left and --right")

compose_lr(args.left, args.right, args.out)

else:

if not (args.top and args.bottom):

raise SystemExit("For --struct tb you must provide --top and --bottom")

compose_tb(args.top, args.bottom, args.out)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Using Flask to create the webpage UI, the character will then be displayed along with a brief description of the radicals that make it up. The main code is primarily in charge of Flask and the three functions that make up the app:

from flask import Flask, request, render_template_string, send_from_directory

import pathlib, time, json, re

from choose_embed import choose # embedding-based radical chooser

from cedict_lookup import search_en # CC-CEDICT English→Chinese lookup

from compose_svg import compose_lr, compose_tb # SVG combiner (⿰ / ⿱)

Flask runs the web server and renders the HTML.

choose_embed is where the SentenceTransformer is called, and the radicals are returned based on semantic similarity

cedict_lookup is used to look up the “real” chinese character in a local file CC-CEDICT dictionary that I downloaded from mdgb.net

compose_svg merges the chosen radicals together

Next the utilities:

The previously created radicals_214.json is loaded once and each radical is resolved to an integer. This is then cached so it doesn’t need to be read after each request.

_id2num_cache = None

def id_to_num_map():

"""Map radical glyph (e.g. '心') and zero-padded numbers ('061') -> int 1..214."""

global _id2num_cache

if _id2num_cache is None:

data = json.loads(RAD_JSON.read_text(encoding="utf-8"))

m = {}

for item in data:

n = int(item["num"])

m[item["id"]] = n

m[f"{n:03d}"] = n

_id2num_cache = m

return _id2num_cache

def normalize_picks_with_nums(picks):

"""Ensure each pick dict has 'num' (int)."""

m = id_to_num_map()

out = []

for p in picks or []:

q = dict(p)

if "num" in q and str(q["num"]).isdigit():

q["num"] = int(q["num"]); out.append(q); continue

if "id" in q and q["id"] in m:

q["num"] = m[q["id"]]; out.append(q); continue

if "num" in q:

digits = "".join(ch for ch in str(q["num"]) if ch.isdigit())

if digits.isdigit():

q["num"] = int(digits); out.append(q); continue

return outThis results in a clean list that looks like so:

[{"id":"心","num":61,"pinyin":"xīn","gloss":"heart","score":0.83}, ...]The sanitize function will be used to make sure that the SVGs I created in Inkscape don’t have any duplicate xmlns attributes:

def sanitize_svg_file(path_obj: pathlib.Path):

"""

Ensure the root <svg> tag has EXACTLY ONE xmlns.

Strategy: remove all xmlns=... attributes from the root tag, then insert one standard xmlns.

"""

try:

txt = path_obj.read_text(encoding="utf-8", errors="replace")

except Exception:

return

m = re.search(r"<svg\b[^>]*>", txt, flags=re.IGNORECASE)

if not m:

return

root = m.group(0)

# strip ALL xmlns="...":

root_no_xmlns = re.sub(r'\s+xmlns="[^"]*"', "", root, flags=re.IGNORECASE)

# add a single standard xmlns after <svg

if "xmlns=" not in root_no_xmlns:

root_fixed = root_no_xmlns.replace("<svg", '<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"', 1)

else:

root_fixed = root_no_xmlns

if root_fixed != root:

txt = txt[:m.start()] + root_fixed + txt[m.end():]

try:

path_obj.write_text(txt, encoding="utf-8")

except Exception:

passNext we have the HTML for the simple webpage. It contains:

- A query box

- A selector for the number of radicals

- A layout selector

- A preview block for the created character SVG

- A table detailing the chosen radicals

- A box displaying the “actual” character

- A link to the composed SVG which opens in a new tab

HTML = """

<!doctype html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Radical Recommender</title>

<style>

body { font: 16px/1.4 system-ui, -apple-system, Segoe UI, Roboto, Helvetica, Arial; margin: 24px; }

form { margin-bottom: 16px; }

input[type=text]{ padding:8px; width:340px; }

select, button { padding:8px; }

table { border-collapse: collapse; margin-top: 10px; }

th, td { border:1px solid #ddd; padding:8px; }

th { background:#f6f6f6; }

.glyph { font-size: 28px; text-align:center; width:64px; }

.muted { color:#666; }

</style>

<h1>Character Creator</h1>

<form method="GET">

<input type="text" name="q" placeholder="Type a word here please" value="{{q or ''}}" autofocus>

<select name="k">

{% for n in [2,3] %}<option value="{{n}}" {% if k==n %}selected{% endif %}>Top {{n}}</option>{% endfor %}

</select>

<select name="layout">

<option value="lr" {% if layout=='lr' %}selected{% endif %}>⿰ left-right</option>

<option value="tb" {% if layout=='tb' %}selected{% endif %}>⿱ top-bottom</option>

</select>

<button>Generate</button>

</form>

{% if composed_name %}

<h2>Composed Character ({{ '⿰' if layout=='lr' else '⿱' }})</h2>

<div style="display:flex;align-items:center;gap:16px;margin:10px 0 18px;">

<img src="/gen/{{composed_name}}" alt="composed glyph"

style="width:256px;height:256px;border:1px solid #ddd;border-radius:8px;background:#fff;">

<div class="muted">

Built from top {{k}} radical{{'' if k==1 else 's'}} using {{ 'left–right (⿰)' if layout=='lr' else 'top–bottom (⿱)' }} layout.<br>

<div><a class="muted" href="/gen/{{composed_name}}" target="_blank">Open composed SVG</a></div>

</div>

</div>

{% endif %}

{% if q %}

{% if picks %}

<div class="muted">Query: <strong>{{q}}</strong> → showing top {{k}} radical{{'' if k==1 else 's'}}</div>

<table>

<tr><th>#</th><th>Radical</th><th>Num</th><th>Pinyin</th><th>English</th><th>Score</th><th>Why this radical?</th></tr>

{% for i, r in enumerate(picks, start=1) %}

<tr>

<td>{{i}}</td>

<td class="glyph">{{r.id}}</td>

<td>{{r.num}}</td>

<td>{{r.pinyin}}</td>

<td>{{r.gloss}}</td>

<td>{{r.score}}</td>

<td>

{% if r.matched_tokens %}<b>matches</b>: {{", ".join(r.matched_tokens)}}{% endif %}

{% if r.fuzzy_tokens %}{% if r.matched_tokens %}; {% endif %}<b>fuzzy</b>: {{", ".join(r.fuzzy_tokens)}}{% endif %}

{% if not r.matched_tokens and not r.fuzzy_tokens %}semantic nearest by embedding{% endif %}

</td>

</tr>

{% endfor %}

</table>

{% if dict_hits %}

<h2>Actual Character</h2>

<table>

<tr><th>Simplified / Traditional</th><th>Pinyin</th><th>Definition(s)</th></tr>

{% for d in dict_hits %}

<tr>

<td style="font-size:28px">{{ d.simp }} <span class="muted">/ {{ d.trad }}</span></td>

<td>{{ d.pinyin }}</td>

<td>{{ "; ".join(d.defs[:3]) }}</td>

</tr>

{% endfor %}

</table>

{% else %}

<p class="muted">No direct CC-CEDICT hit for “{{q}}”. Try a near synonym.</p>

{% endif %}

{% else %}

<p>No results (this shouldn’t happen yoink). Try another word.</p>

{% endif %}

{% else %}

<p class="muted">Create your own pictogram for only 79.99 a month!</p>

{% endif %}

"""The composition function ensures that at least two characters are picked and ensures a safe output filename for the SVG based on the word and the timestamp. Functions from the compose_svg.py script are called here depending on whether the user chooses two or three radicals:

def compose_new_character(word, picks, layout="lr"):

"""

Compose 2 or 3 radicals into one SVG and return the output filename.

layout: 'lr' (⿰) or 'tb' (⿱). For 3 parts we nest; on error we fall back to 2.

"""

if not picks or len(picks) < 2:

return None

def fp(n: int) -> str:

return (ROOT / "svg" / f"{int(n):03d}.svg").as_posix()

OUT_DIR.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

stamp = int(time.time())

base = "".join(ch for ch in (word or "generated").lower() if ch.isalnum() or ch in "-_") or "generated"

n0, n1 = int(picks[0]["num"]), int(picks[1]["num"])

# 2 components

if len(picks) == 2:

out_name = f"{base}_{layout}_{stamp}.svg"

out_path = (OUT_DIR / out_name)

if layout == "lr":

compose_lr(fp(n0), fp(n1), out_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

else:

compose_tb(fp(n0), fp(n1), out_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

sanitize_svg_file(out_path)

print(f" Wrote {out_path}")

return out_name

# 3 components with nesting; sanitize the temp before re-parse

n2 = int(picks[2]["num"])

tmp_path = OUT_DIR / f"tmp_{base}_{layout}_{stamp}.svg"

try:

if layout == "lr":

# ⿰( n0 , ⿱( n1 , n2 ) )

compose_tb(fp(n1), fp(n2), tmp_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

sanitize_svg_file(tmp_path) # <-- fix duplicate xmlns before re-using

out_name = f"{base}_lr3_{stamp}.svg"

out_path = OUT_DIR / out_name

compose_lr(fp(n0), tmp_path.as_posix(), out_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

else:

# ⿱( n0 , ⿰( n1 , n2 ) )

compose_lr(fp(n1), fp(n2), tmp_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

sanitize_svg_file(tmp_path) # <-- fix duplicate xmlns before re-using

out_name = f"{base}_tb3_{stamp}.svg"

out_path = OUT_DIR / out_name

compose_tb(fp(n0), tmp_path.as_posix(), out_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

sanitize_svg_file(out_path)

print(f"Wrote {out_path}")

try:

tmp_path.unlink(missing_ok=True)

except Exception:

pass

return out_name

except Exception as e:

print(f" 3-part compose failed ({e}). Falling back to 2-part.")

out_name = f"{base}_{layout}_{stamp}.svg"

out_path = OUT_DIR / out_name

if layout == "lr":

compose_lr(fp(n0), fp(n1), out_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

else:

compose_tb(fp(n0), fp(n1), out_path.as_posix(), size=1024, gutter_ratio=0.0)

sanitize_svg_file(out_path)

print(f"Wrote {out_path} (fallback 2-part)")

return out_nameThe main function:

1) Grabs the input from the URL (e.g. “?q=knowledge&k=2&layout=lr”)

2) Calls the choose function from choose_embed.py where the transformer is invoked to embed the query. Here is also where the NumPy functions are called to do the comparison maths.

3) The normalize_picks_with_nums function converts the radicals “id” from the radicals_214.json into an int which allows the app to find the correct radical SVG.

4) The search_en function in my cedict_lookup.py script then searches the downloaded dictionary for the “real” character.

5) The new glyph is composed by the aforementioned compose_new_character function

6) The webpage is rendered via Flask’s render_template_string function

def index():

q = (request.args.get("q") or "").strip()

layout = (request.args.get("layout") or "lr").lower() # 'lr' or 'tb'

try:

k = int(request.args.get("k") or "2")

except ValueError:

k = 2

picks_raw = choose(q, k) if q else None

picks = normalize_picks_with_nums(picks_raw)

dict_hits = search_en(q, limit=1) if q else []

composed_name = None

if q and picks and len(picks) >= 2:

composed_name = compose_new_character(q, picks, layout=layout)

return render_template_string(

HTML,

q=q,

k=k,

layout=layout,

picks=picks,

dict_hits=dict_hits,

composed_name=composed_name,

enumerate=enumerate

)The Result:

At the very least, the app managed to produce some amusing combinations:

Required fixes:

At the moment the app only combines radicals in their full form, (for example, the “heart” + “sweet” character for “love” would more realistically look like: “忄甘“, with the side version of the heart radical being used instead of the main character). Fixing this would require an overhaul of the local files created for the app to calibrate for some of the 214 having two or more versions based on where they are expected to appear on the final character. (The app already keeps note where each radical is being placed, which is why the radicals on the left of the character appear slimmer than the ones on the right).

The other major problem can be seen in the “Actual Character” section where the proper character for the word is supposed to be shown. English and Chinese do not easily lend themselves to being translated via a direct and simple word search. My cedict_lookup.py script basically just scours the dictionary for the inputted word and outputs the first entry it finds. This results in inaccuracies like the word 宠 (chong) which is presented here for “love”. This character is actually part of the word 宠物 (chongwu) which means “pet” (literally “a creature that you pamper”) as in a cat or a dog (or a TigerFrog). It would make more sense here to use the character 爱 here, whose meaning is much closer to the English conception of “love”. A more intelligent system is required here to produce the suitably correct character for comparison. This might require connecting the app up to an LLM for that specific purpose alone. (A breakdown of the radicals which make up the actual Chinese character would also be a complicated but illuminating addition to the app). At present I would keep the semantic-searching sentence-transformer model for choosing the radicals for the new glyphs, if for no other reason that it has entertained me suitably thus far.

In Conclusion:

In conclusion I am absolutely no nearer to anything like a conclusion. At present the app is my crude attempt to get an AI model to produce something vaguely “artistic” without letting it know that that is what it is actually doing.

Just like the “artist” who is more concerned with being an “artist” than creating art is of little interest to me, a designated “art-creating” AI has of yet failed to capture and hold my imagination. I am however currently circling the formulation of a thesis around the idea that an AI model unaware that it is creating art, might actually be able to create some.