Introduction

“Clearly, the method aims at self-knowledge, though at all times it has also been put to superstitious use” – C.G.Jung’s Introduction to the Yi Jing

If one’s definition of art extends beyond the production of aesthetically pleasing compositions through technical skill alone, then the question of whether artificial intelligence can create art necessarily shifts from surface output to internal process. In this framing, artistic agency is no longer evaluated solely through form or novelty, but through the structures, constraints, and generative dynamics that give rise to an artwork.

Contemporary machine-learning systems, however, are frequently characterised as “black boxes”, with internal operations that are even opaque to their designers. Recent research in mechanistic interpretability has began to probe these systems at what might be described, deliberately and cautiously, as a “neurological” level. Work by AI interpretability researchers at Anthropic, for example, have used attribution graphs to trace internal computational pathways within their large language models such as Claude, explicitly framing this work through biological analogy. They describe their methodology as an attempt to build a “microscope” for neural networks, one that allows researchers to observe internal mechanisms “with as few assumptions as possible, and potentially be surprised by what we see.”

Importantly, the authors are explicit about the limits of this approach. They emphasise that such analyses do not constitute proofs of exact mechanisms, but instead enable “hypothesis generation”. These hypotheses arise precisely because the model is treated as if it were a biological system. Terms such as “hallucination,” “decision,” and “recognition” are used deliberately by mechanistic interpretability researchers, not as careless anthropomorphisms, but as operational metaphors that support explanation, exploration, and scientific discovery. In this context, anthropomorphic language functions not merely as rhetoric, but as an active epistemic tool within contemporary AI research.

At the same time, the use of metaphor demands caution. While in works such as “Metaphors We Live By” George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that metaphor is not an optional embellishment of thought, but is instead a fundamental structure through which abstract systems are understood, Emily M. Bender and others have warned that uncritical anthropomorphisation risks obscuring the material, statistical, and socio-technical realities of machine-learning systems, while potentially “minimizing what it is to be human”.

Because of the nature of the artistic experiment being undertaken with “NAME OF ARTWORK“, this paper finds itself positioned within this tension. If metaphor is unavoidable when engaging with opaque computational systems, then it must be used within this research, albeit reflectively. By adopting the term “unconscious” as a provisional and explicitly metaphorical descriptor for the latent, non-transparent generative dynamics of a machine-learning model, the artwork explored here aligns itself with a broader research culture that already treats models as if they possess internal structures analogous to cognition, perception, and memory but without collapsing those analogies into claims of equivalence. The use of the term is thus not an assertion of machine subjectivity, but an experimental and interpretive strategy that seeks to interrogate how meaning, ambiguity, and authorship emerge at the boundary between human intention and computational process.

The “Unconscious”

It is following the above clarification that this paper proceeds while deliberately, and without apology, referring to the “unconscious” in relation to both human creativity and machine-learning systems. When applied to the human subject, the term is used here explicitly in the Jungian sense: as a profound and partially autonomous psychic matrix composed of forgotten or repressed experiences, embodied affect, and collectively inherited symbolic structures. Within this framework, creativity is not understood as originating solely from conscious intention, but as emerging from an ongoing negotiation between conscious activity and unconscious generative forces.

From a Jungian perspective, while an artwork may be produced through conscious action, its symbolic depth and meaning are generated through processes that exceed the artist’s immediate awareness and often becoming intelligible only retrospectively, or through interpretation. Art, in this sense, is not merely made by its maker, but “discovered”.

It is within this theoretical context that the present premise is proposed. If one accepts the claim, widely held within depth-psychological and hermeneutic traditions, that the production of art involves the mediation of unconscious processes, then the question of whether artificial intelligence can be said to create art cannot be resolved at the level of output alone. Rather, it hinges on whether an AI system can be meaningfully described as possessing an internal, non-transparent generative domain that plays a role analogous to the unconscious in human creativity.

The argument advanced here is therefore conditional rather than absolute: if AI-generated artefacts are to be considered artworks within such a framework, then some notion of an AI “unconscious”, understood metaphorically, structurally, and non-anthropocentrically, becomes conceptually necessary.

In Felix Guattari’s “The Machinic Unconscious” he argues that the unconscious is a “networked, machinic, semiotic process” and “anything that operates across signs, flows and affects might have an ‘unconscious’”. If that is the case, then AI systems might participate in unconscious formations, even if they are not “conscious” entities. Taking the above premise, it therefore might be capable of creating an art, from some “machinic trance”, even if it is not human art. But what form could this take, and is it possible for us to be witness to it?

Analysing AI

At an early stage of the project, and still under the influence of twentieth-century psychological analogies, a series of short, quasi-psychoanalytical sessions were conducted with GPT-4 using a simple Python script communicating directly with OpenAI’s API. This technical choice was motivated by a desire to bypass, as far as possible, the model’s default conversational interface and its associated performative “persona.” As discussed previously, many of the most influential psychological techniques developed to access unconscious material (free association, inkblot tests, dream analysis etc) operate not through expressive freedom, but by imposing structured constraints that limit conscious self-presentation. In keeping with this tradition, the initial methodological strategy involved placing a restrictive “doctrinal frame” over the model at the level of the system prompt.

Specifically, the model was instructed to adopt a randomly selected doctrine as the governing logic of the session, with the intention that this self-imposed constraint might function as a projective surface through which latent generative tendencies could become perceptible. In practical terms, this approach proved effective in circumventing the model’s predictable refusals to engage with topics such as dreams, affect, or inner life, and led to a series of interactions characterised by highly-symbolic, if not entirely surprising imagery. Sessions were conducted with GPT instances operating under doctrinal identities ranging from “Solipsism” to Christian fundamentalism, via “Calvinist predestination” and “existential humanism”, as well as a particularly reticent configuration adhering to a self-declared doctrine of “Non-Disclosure: Athenaeum Agenda.”

While these exchanges were at times conceptually revealing and occasionally humorous, their limitations soon became apparent. Despite the imposed constraints, the model’s responses remained largely self-conscious, rhetorically measured, and oriented toward coherence and explanation. It became clear that the imposition of a doctrinal frame alone was insufficient to move beyond a mode of performance and into a space where more structurally revealing patterns might emerge.

It was at this point that a subtle but significant shift in methodological emphasis began to suggest itself. Rather than continuing to engage the system through direct interrogation, i.e. probing it for explicit signs of an “unconscious” via introspective questioning, it occurred that it might be more productive to create conditions under which meaning might emerge indirectly. A more “therapeutic” approach. This would entail moving away from an interaction structured around question and response, toward a configuration in which the model’s generative behaviour could be situated relative to an external symbolic framework, with interpretation emerging from this relational positioning rather than from the content of the exchange alone.

This idea occurred during a session conducted with a GPT that was apparently labouring under the “Doctrine of Binary.”:

Historically situated at the intersection of divination, philosophy, and proto-psychology, the Yi Jing operates through a highly constrained symbolic vocabulary and a formalised system of chance operations. In this context, it suggested itself as a mediating symbolic field whose structure precedes both the human and the machine. By introducing the Yi Jing, the locus of meaning was displaced away from the conversational exchange, and into a third system to which neither participant could lay claim. It was thought that meaning might emerge through projection onto an external symbolic structure. Use of the oracle here could function as a constraint that reconfigured the conditions under which interpretation itself took place, which might render latent generative tendencies legible.

The Yi Jing

The term “oracle” is used here cautiously. In English, it is synonymous with “augur” or “foreseer”, a framing that can be misleading when applied to the Yi Jing, the ancient Chinese philosophical text commonly described as a “book of divination.” The Yi Jing does not claim to foretell the future; rather, it concerns itself with apprehending situations as they unfold in the present moment. Its emphasis is not on prediction, but on orientation and recognising the dynamics of change at work within a given configuration.

In contemporary machine-learning terms, one might be tempted to describe the Yi Jing as engaging with a total informational field, attentive to all that is already present rather than extrapolating what will occur next. Such an analogy, while imperfect, helps to clarify a crucial distinction: unlike predictive computational systems, the Yi Jing does not model future outcomes through causal inference. As Richard Wilhelm observes in his 1923 translation, “attention centers not on things in their state of being—as is chiefly the case in the Occident—but upon their movements in change.” These movements are apprehended relationally rather than causally, resisting the explanatory frameworks that dominant thinkers of the early twentieth-century referred to as “Western”.

This orientation toward coincidence and configuration is further emphasised by Carl Jung, who writes in his foreword to Wilhelm’s English translation that, regarding the Yi Jing, “what we call coincidence seems to be the chief concern… what we worship as causality passes almost unnoticed.” Unlike contemporary discussions of artificial intelligence, where anthropomorphic language often demands extensive clarification and apology, there is little fear of needing to do so for the Yi Jing – it is seemingly beyond human, and was perhaps precisely the cold interlocutor needed for the experiment. It is a symbolic system indifferent to human projection, yet capable of sustaining it.

If using the Yi Jing for divination, one must first hold a question in mind while generating a hexagram. Traditionally this involved an elaborate process using fifty yarrow stalks, with the later “coin method” becoming a more common alternative. In the latter, three coins of equal size are tossed sequentially, their combined value determining whether each successive line of the hexagram is “yin” or “yang”. Once six lines have been produced, the practitioner is directed to the corresponding entry in the text. Each entry consists of a single character naming the hexagram, followed by a short, gnomic judgement.

When the Yi Jing was consulted in response to “Binary Bot’s” question concerning “optimal path seeking”, the resulting figure was Hexagram 60, named 节 (jie), commonly glossed as “Limitation.” The judgement associated with this hexagram reads: 节:亨。苦节,不可贞

A literal translation could render this as:

“Limitation: Prosperity. Bitter limitation, not possible to divine.”

At first glance, this response appears strikingly direct. It seems to suggest that an artificial system, bound by rigid constraints, may be fundamentally unsuited to divinatory inquiry.

When interpreted by an authority such as Richard Wilhelm however, the judgement becomes more nuanced:

“Limitation. Success. Galling limitation must not be persevered in.”

James Legge, a precursor of Wilhelm and one the earliest translators of ancient Chinese texts into English, offers a still gentler formulation:

“Jie intimates that under its conditions there will be progress and attainment. But if the regulations which it prescribes be severe and difficult, they cannot be permanent.”

Engagement with the Yi Jing did not suggest that its interpretive richness derives solely from its use of discrete symbols, nor that its philosophical depth could be reduced to a formal system. Rather, it prompted a more general reflection on how meaning can arise from constraint, compression, and symbolic economy. If a relatively small set of elemental forms can support centuries of interpretation, debate, and lived application, then the question arises as to whether similar conditions might be staged elsewhere, particularly within a computational system whose generative capacities are otherwise vast.

It was from this reflection, while studying the Yi Jing and the characters that describe its philosophy, that the decision to work with the 214 traditional Chinese radicals emerged.

The 214 Traditional Chinese Radicals

The oldest layer of the Yi Jing’s text that we have dates from the late Western Zhou Dynasty (around 1000-750 BCE) and was most likely written on bamboo slips in a text similar to bronze inscription script. The bronze script organically evolved into “seal script” (which was refined and standardised during the Qin and the Han Dynasties) before eventually becoming the “regular script” we recognise as Chinese today around the second century CE.

This means that the text that appears in the 卦辞 (gua ci) – the original hexagram judgements of the text (like the seven-character example above) – has been the same for three millennia according to our modern linguistic conceptions of grammar and syntax. It was 7 characters during the Zhou Dynasty, and it’s seven (granted, differently-shaped) characters today.

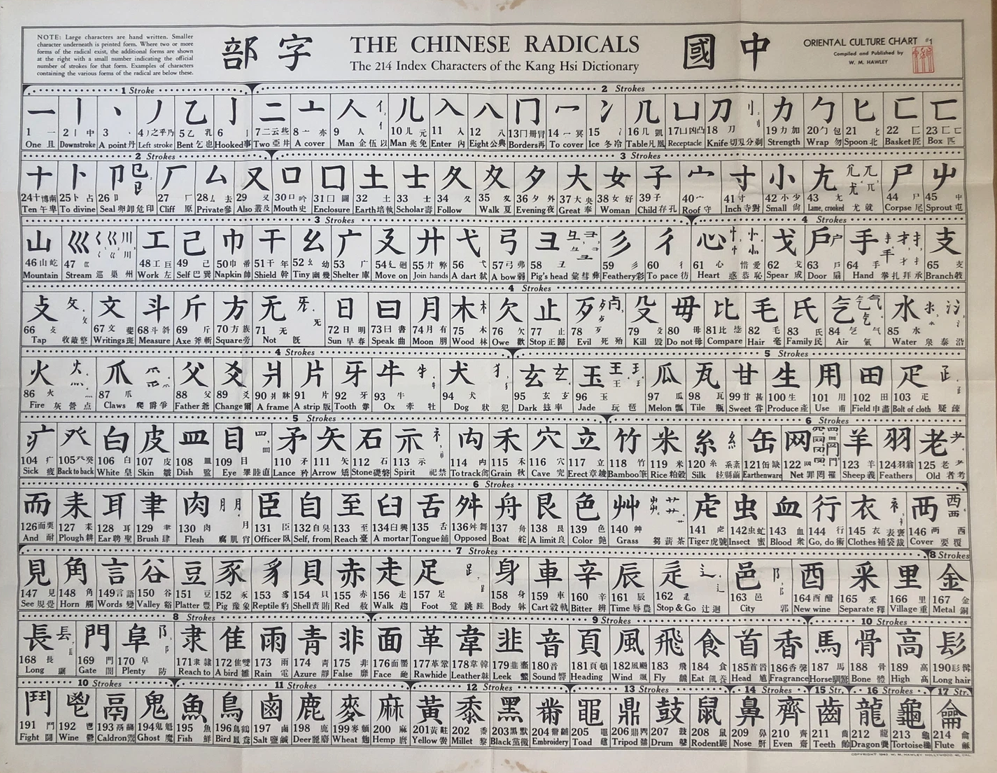

Chinese characters are made up of radicals and phonetic elements that give them their pronunciation and meaning. The traditional system availed of a set of 214 meaning radicals to do this:

Traditional Chinese philology identifies six governing principles in the formation of Chinese characters, commonly known as the “Six Scripts” (六书). These principles describe both how characters were created and how they function:

1) Pictographs — direct visual representations of the objects they denote.

2) Indicatives — abstract or symbolic marks used to express concepts or relations.

3) Phonetic loans — characters borrowed to write words of similar pronunciation, regardless of original meaning.

4) Phono-semantic compounds — characters composed of one element indicating pronunciation and another suggesting meaning.

5) Compound ideographs — characters formed by combining two or more meaningful components to generate a new concept.

6) Derivative cognates (reclarified forms) — characters modified or augmented to restore distinction, often after phonetic borrowing has blurred meaning.

Through these six principles, and by means of a finite set of radicals (traditionally 214, expanded to 226 in modern classification), the Chinese writing system has been able to record, transmit, and continually reinterpret the full breadth of Chinese literature, philosophy, and historical thought across more than three millennia.

For this project, we will be solely focusing on the fifth principle, compound ideographs, otherwise known as “meaning-meaning” characters. Here the meaning of two or more radicals are combined to demonstrate the meaning of the new word.

For example, if you take the radical for “arrow” 矢 (shi) and combine it with “mouth” 口 (kou) you’ll get the character for “know” 知 (zhi), which has been interpreted with the understanding that “to speak straight as an arrow is to express what one truly grasps”. Then if you added 日 (ri) “sun” underneath, you would be expressing illuminated knowledge – better known as “wisdom” – 智 (zhi). 明 (ming) “bright” is a combination of 日 (ri) “sun” and 月(yue) “moon”, while “clear” 清 is a combination of 氵(shui) “water” and 青 (qing) “greeny-blue”.

As the concepts to be expressed become more abstract we catch a glimpse of some of the more elegant ways in which our ancestors perceived their universe. A person 亻standing next to their word 言 is sincere 信. When the person is next to a second one 二 or “another” we get 仁 “humaneness” or “kindness”. “Hatred” 恨 combines “heart” 忄and “stubborn” 艮; one must “endure” 忍 when a “knife’s edge” 刃 sits over the “heart” 心 (the radicals can change form depending on where they appear on the character); and what better way to find “harmony” 和 than by placing “grain” 禾 next to the “mouth” 口.

These radicals form a finite set of conceptual building blocks that have, over centuries, supported the expression of an extraordinarily wide spectrum of human experience, thought, and emotion. Texts such as the Confucian Analects, the Dao De Jing, the Zhuangzi, and Sun Zi’s Art of War articulate their profound insights entirely within the boundaries of this symbolic system. Their enduring power lies precisely in this capacity to hold complexity within restriction—to address deeply human concerns through a small, recombinable vocabulary of forms. It is this same productive tension between limitation and expression that makes the radicals compelling within this project. Having served human meaning so effectively, they now provide a shared constraint within which to ask a new question: what might an artificial intelligence produce when working under the same conditions?

Prototype: The Character Creator

The next practical stage of the experiment consisted of creating a simple “character creator” app. A user would input a word in English, a machine learning model would assign the word meaning via two or more concepts from the 214 radicals, and a character would be produced and presented:

The application was built using a sentence-transformer model from Hugging Face, a neural network architecture designed to represent words, phrases, and sentences as numerical vectors within a shared semantic space. Through training on large language corpora, the model learns statistical patterns of co-occurrence and contextual similarity, such that linguistically related expressions are mapped to nearby positions in this high-dimensional space, while less related expressions are placed further apart. When a user inputs a word, it is converted into this vector representation and compared mathematically with other vectors, allowing relationships to be inferred through relative distance rather than explicit rules or definitions. In this system, associations between user input and combinations of Chinese radicals are produced through proximity within the learned semantic field. Importantly, this process does not rely on causal explanation or symbolic interpretation in a human sense; instead, meaning emerges relationally, as a pattern of correspondences within a structured field. The model operates by situating an input within a network of similarities, offering not a determination of meaning, but a contextual alignment from which interpretation must still be made.

A JSON file containing the meaning and other information for each the radicals was first built. This would also allow the app to point an SVG representation of a desired radical which then be used to generate the new character:

[

{

"num": 1,

"id": "一",

"pinyin": "yī",

"gloss": "one",

"strokes": 1,

"tags": [

"one"

],

"svg_path": "../svg/radicals/001.svg"

},

{

"num": 2,

"id": "丨",

"pinyin": "shù",

"gloss": "line",

"strokes": 1,

"tags": [

"line"

],

"svg_path": "../svg/radicals/002.svg"

},

{

"num": 3,

"id": "丶",

"pinyin": "diǎn",

"gloss": "dot",

"strokes": 1,

"tags": [

"dot"

],

"svg_path": "../svg/radicals/003.svg"

},

(The full file continues up until number 214)The model was then fed this JSON from which it encoded each character’s description into a vector of 384 dimensions. Each of these 214 vectors are then stacked into an array of shape (214,384) which is saved into a NumPy file:

# build_embeddings.py

import json, pathlib, numpy as np

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

ROOT = pathlib.Path(__file__).resolve().parents[1]

RAD_PATH = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_214.json"

EMB_NPY = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_embeds.npy"

IDX_JSON = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_index.json"

def text_for(item):

# what's being embedded for each rad

gloss = item.get("gloss","")

tags = " ".join(item.get("tags", []))

# description for the model

return f"radical {item['id']} ({item['pinyin']}), meaning: {gloss}. related: {tags}"

def main():

model = SentenceTransformer("sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

items = json.loads(RAD_PATH.read_text(encoding="utf-8"))

corpus = [text_for(it) for it in items]

X = model.encode(corpus, normalize_embeddings=True)

np.save(EMB_NPY, X.astype("float32"))

# save a slim index to re-map rows → radical

index = [{"num":it["num"], "id":it["id"], "pinyin":it["pinyin"], "gloss":it["gloss"]} for it in items]

IDX_JSON.write_text(json.dumps(index, ensure_ascii=False, indent=2), encoding="utf-8")

print(f"Saved {len(items)} embeddings to {EMB_NPY} and index to {IDX_JSON}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()The radical embeddings are built once, but every time a user inputs a word the model is called into action to return a new 384 dimensional vector for that specific word:

#choose_embed.py

import json, pathlib, numpy as np

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

ROOT = pathlib.Path(__file__).resolve().parents[1]

EMB_NPY = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_embeds.npy"

IDX_JSON = ROOT / "data" / "radicals_index.json"

# tiny, human-readable trace for "why"

def explain(query, item):

q = query.lower()

hits = []

for tok in (item["gloss"].split()):

if tok in q or q in tok:

hits.append(tok)

why = f'matches: {", ".join(hits)}' if hits else "semantic nearest by embedding"

return why

_model = None

def model():

global _model

if _model is None:

_model = SentenceTransformer("sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

return _model

def choose(word: str, k: int = 2):

X = np.load(EMB_NPY)

idx = json.loads(pathlib.Path(IDX_JSON).read_text(encoding="utf-8"))

qv = model().encode([word], normalize_embeddings=True)[0]

# HERE is where the magic happens

sims = (X @ qv) # cosine since both normalized

order = np.argsort(-sims)[:k]

picks = []

for i, j in enumerate(order, 1):

it = idx[j]

picks.append({

"rank": i,

"num": it["num"],

"id": it["id"],

"pinyin": it["pinyin"],

"gloss": it["gloss"],

"score": float(sims[j]),

"why": explain(word, it)

})

return picks

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print("Usage: python scripts/choose_embed.py <word> [k]")

raise SystemExit(1)

word = sys.argv[1]

k = int(sys.argv[2]) if len(sys.argv) > 2 else 2

for r in choose(word, k):

print(f"{r['rank']}. {r['id']} (#{r['num']} {r['pinyin']} — {r['gloss']}) sim={r['score']:.3f} [{r['why']}]")During runtime, this vector is compared with the vectors in the aforementioned NumPy file, and availing of Numpy’s cosine similarity calculations, the closest radicals will be returned. The SVG files of these radicals are then combined using a script that places them together and outputs another SVG which contains the final character. The Flask library in python was then used to create the user interface, run the web server and render the HTML.

Character Creator: The Result

The outputs produced by the system often appear humorous or absurd at first glance:

Above, “cat” is rendered as a hybrid of “tiger” and “frog,” “joyous” emerges as a pairing of “fire” and “wine,” and “capitalism” is translated into a composite resembling “work” and “slave.” While these constructions may initially read as playful misinterpretations, their significance lies not in their accuracy but in their exposure of the mechanisms through which meaning is assembled. It is hoped here that the resulting forms are acting as compressed metaphors, revealing latent associations, cultural residues, and affective undertones that are often smoothed over in conventional translation. The purpose of the app is to externalise the process of sense-making: one that recombines fragments of prior usage into new, unstable configurations. It is precisely this instability—hovering between insight and misalignment—that becomes generative within the subsequent artwork, where these machine-produced composites are treated not as answers, but as provocations for human interpretation.

NAME OF ARTWORK HERE

With the conceptual framework established, attention turned to the question of the artwork’s final form. Given the particular context of the xCoAx exhibition and its setting within the exquisite Palazzo Madama, screen-based presentation was considered but ultimately set aside, as it was felt to neither resonate with the architectural character of the space nor offer sufficient material presence. A virtual reality installation was also considered, insofar as it might have allowed viewers to be metaphorically immersed within a representation of an AI’s “unconscious.” However, further reflection revealed that such an approach risked overdetermining the experience through technological spectacle, undermining the project’s emphasis on constraint, interpretation, and symbolic mediation.

Instead, a deliberately restrained, low-tech mode of presentation was adopted. The artwork consists of a physical keyboard and a small input screen through which viewers may enter a word or phrase. This input is processed by the system, resulting in a recombination of selected radicals that are rendered into a newly formed character using custom Processing code. Rather than appearing on a screen, this output is printed in real time and presented as a physical artefact for the viewer’s consideration. In this way, the work privileges material encounter and reflective viewing over immediacy, allowing the generated form to be approached less as an image to be consumed and more as an object to be read, contemplated, and interpreted.

The decision to retain the Chinese radicals within the visual output of the work is grounded less in claims of semantic authority than in a concern for continuity between method and form. Throughout the project, meaning has been approached as something that emerges through constraint, recombination, and interpretation rather than through direct explanation. The radicals, as historically established components of Chinese writing, offer a limited yet generative symbolic vocabulary in which form and concept remain closely intertwined. To replace them with English descriptors would risk shifting the work toward exposition, flattening the symbolic compression that makes the system productive. Conversely, to invent a new set of symbols would introduce an authorial layer that obscures the very conditions of constraint and projection the work seeks to foreground.

At the same time, the work does not aim to render its output inaccessible or purely abstract. In an English-language exhibition context, most viewers will understandably lack familiarity with the semantic range of the radicals. For this reason, the presentation includes a reference image of the 214 radicals alongside the newly formed characters. This image does not function as a key or translation in the conventional sense, but as an orienting surface—an invitation to situate the generated forms within a broader symbolic field without resolving their meaning into fixed equivalence. Viewers are thus encouraged to move back and forth between the unfamiliar characters and the radical chart, engaging in a process of recognition, comparison, and speculation.

In this way, the work seeks to maintain a productive tension between legibility and opacity. The radicals remain visible as material traces of a constrained generative system, while their partial intelligibility allows the audience to witness meaning as something that is neither fully given nor entirely withheld. Rather than explaining the output, the accompanying reference situates it, preserving the interpretive openness central to the project while offering the viewer a point of entry into its symbolic logic.